A few days earlier, I was in a small plane flying over the deep green forests of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The plane shook violently from turbulence as it approached Keweenaw Bay, a V-shaped inlet on the southern shore of the lake. A thin layer of smoke had settled on the water, blown in from wildfires burning hundreds of miles away in Canada.

The lake tribes live in close-knit communities that I knew I’d need help to access. So, I retained a local, Charlie Rasmussen, to advise me on various aspects of the trip: He warned me about spotty cellphone coverage, which roads were under construction and where deer liked to dart out in front of traffic; he also gave me leads on locals I could speak to about fishing. (He is a writer, photographer and communications officer for the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, a nonprofit that supports member tribes through natural resources management, conservation and public information. But his work with me was in a freelance capacity.)

A rental car secured, I drove an hour south along Highway 41, to the L’Anse Reservation, where a pocket of woods was quiet but for water spilling over a mossy rock ledge. Jerry Jondreau was trying to catch brook trout on Silver River, which twists its way through the reservation. The reservation is home to the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC), one of about a dozen bands, including the Bad River Band, who live around the lake.

The lake itself is often hailed for being the cleanest of the Great Lakes. But Jondreau said its pristine reputation is a misconception. “I can’t bring fish back to the family from the lake,” he explained. “We don’t eat as much fish as we used to.”

Lake Superior is the largest freshwater lake on Earth by surface area, spanning a vast 31,700 square miles. Surrounded by dense forests and relatively sparse populations, more than 80 species of fish live in its cold, remote waters. While the fish are abundant, they’re rife with contaminants: polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins, the pesticide toxaphene — all linked to cancer — and mercury, left behind as a legacy of mining in a rugged region known as Copper Country. There are enough pollutants now circulating in the great lake that Michigan lists more than a dozen consumption advisories for its fish, and the pollution runs headlong into areas where tribes practice subsistence fishing.

On a windy August afternoon, the choppy waters around Lake Superior’s Madeline Island glittered with flecks of sunshine. Boats headed north, fishing poles straining toward wakes churning behind them. In 2019, Wisconsin scientists took samples from fish swimming near the island, considered the spiritual homeland of the Ojibwe. Six fish species had detectable levels of PFAS — and rainbow smelt had an average of seven times the amount of PFAS that were found in the other fish, according to data from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. It was enough to trigger the January 2021 consumption advisory for Wisconsin waters. Two months later, Minnesota and Michigan followed suit with their own advisories.

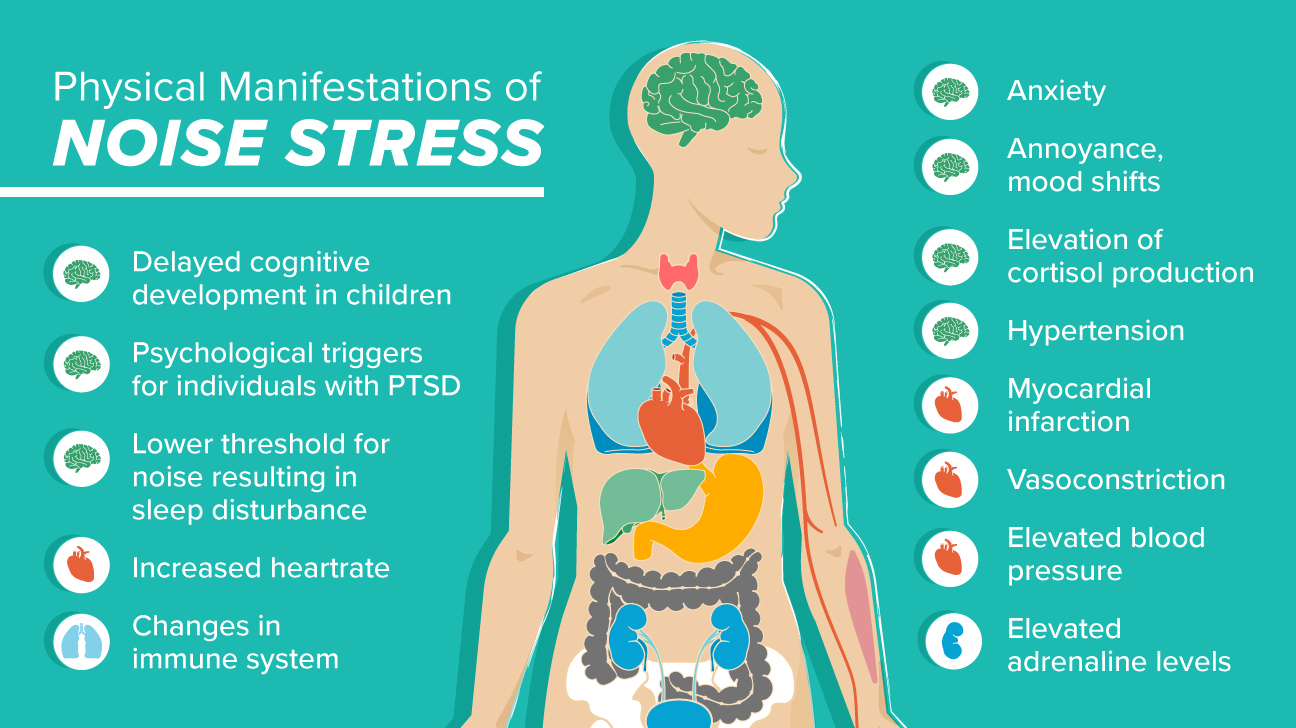

PFAS were introduced to Americans in the 1940s. Prized for their resistance to heat, oil and water, they were key ingredients in products like Scotchgard and Teflon. Today, they’re found in food packaging, carpets, furniture, clothing, makeup and everyday household items like dental floss. They’re used on an industrial scale in nonstick and waterproof coatings, electronics, degreasers and fire foams. The chemicals have been linked to a host of serious health problems: high cholesterol, liver damage, suppression of the immune system, thyroid disease, kidney and testicular cancer, among others, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Some take years to be eliminated from the human body.

“They dissolve easily in water,” says environmental engineer Christy Remucal, who studies PFAS in her lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. (Remucal was not involved in the testing of the Lake Superior fish.) So, the chemicals move around the environment fairly easily, she told me — and there are thousands of them. One of these, called PFOS, or perfluorooctane sulfonic acid — found at airports and military sites with histories of fire foam use — tends to build up in fish.

But Michigan scientists were puzzled when the little smelt showed higher levels of PFOS than larger, predator fish such as lake trout. “Typically, the higher up on a food chain that you go, you’re going to have higher levels of contamination,” explains Brandon Armstrong, an aquatic biologist with the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), referring to a process called biomagnification. “It was surprising to see such a high level of PFOS in smelt because they feed low on the food chain,” he says. “They’re eating small fish and zooplankton out in the glades. They’re not a top-predator species.”

Smelt is just one among many fish that tribal communities in the lake basin depend on. Indeed, food sovereignty was a cornerstone of 19th-century treaties in which the Ojibwe ceded millions of acres and retained their rights to fish, hunt and gather. These rights were challenged a century later, when William Jondreau, an Ojibwe man — and grandfather of Jerry Jondreau — was arrested for catching lake trout when it was out of season. He claimed, under treaty rights, that he was free to fish on Keweenaw Bay, where his people had fished for centuries. His case went before the Michigan Supreme Court and, in the 1971 landmark Jondreau decision, the court ruled that the 1854 treaty with the Chippewa superseded state fish and game laws.

The decision reaffirmed his people’s right to hunt and fish on ceded territories. But there has been a steady “devaluation” of treaty rights since, Jerry Jondreau argues. “In those agreements, we retained our rights to hunt, fish and gather,” he says. “In exchange, the U.S. got all the land. It’s accruing wealth. But the fish, the water … those things are becoming sick.”

On the Bad River Reservation, a flash of lightning lit up a dark cloud over the Kakagon River. Seconds later, a low rumble of thunder rolled through the wetlands. Edith Leoso watched from the back of the boat as it sped inland. The rice harvest would be plentiful this season, she said. But the smelt population is in decline — and has been for years. Even so, she said, “people are still smelting when they shouldn’t be. We should leave that fish alone.” They’re fishing out of necessity,she explained, regardless of consumption advisories: “We don’t recognize them if we have to feed our families. That’s the bottom line.”

Michiganalso lists consumption guidelines for fish in hundreds of smaller lakes and rivers. “Fishing is a primary source of subsistence for Ojibwe tribes throughout the basin,” says Valoree Gagnon, director of university-Indigenous community partnerships at the Great Lakes Research Center of Michigan Technological University. “So, when you’re asked to lower fish consumption, you’re not just losing meals, you’re losing all those practices associated with fishing: sharing knowledge and passing that to future generations. It changes all kinds of social dynamics.”

The lake tribes have been proactive in response to environmental threats to their water. In 2009, the Environmental Protection Agency gave the Bad River Band the authority — known as “treatment as a state” — to set its own water-quality standards. A decade later, KBIC received the same authority.

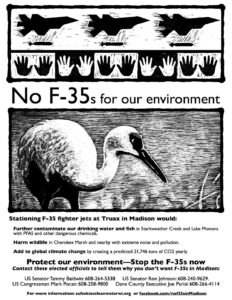

Researchers are doing additional testing to identify possible sources of PFAS in Lake Superior. But contaminated sites already identified may hold clues. The chemicals have been found at the Duluth Air National Guard Base, adjacent to a PFAS-polluted creek that leads to Saint Louis Bay, at the southwestern corner of the lake in Minnesota; they were first detected at the Duluth air base in 2010, said Bioenvironmental Manager Maj. Ryan Blazevic of the 148th Fighter Wing in an email. The wing “no longer conducts fire protection training in a manner that discharges firefighting foam,” he said. (Firefighter training is a common source of PFAS at military bases.)”

find more at this link much more to the story