Paulius Musteikis

Assumption Greek Orthodox Church looks like a typical orthodox church with a traditional, though rather subdued, cupola dome. Despite its unassuming shell, the blond brick church at the corner of East Washington Avenue and 7th Street houses one of the region’s most spectacular artistic achievements, a sprawling and breathtaking work of Byzantine iconography. Perhaps most impressive, it is the work of one artist.

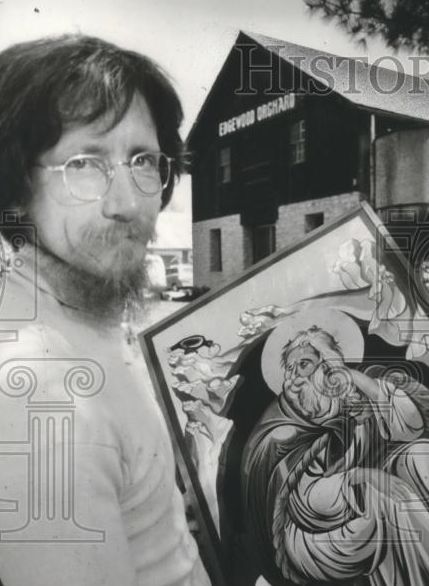

David Giffey, a bearded 75-year-old journalist, veteran and peace activist, has been painting portions of Assumption for the last 39 years.

For Giffey, art and religion are intertwined. “Planning and painting icons for the Madison church has given me a way to bring life and work together,” he says. “I’m an artist, and I have a need for a spiritual life as well. So being commissioned to make icons has provided both physical and spiritual sustenance.”

Parish member Eleni Schirmer recalls Giffey teaching her childhood Sunday school classes. “He brought these saints to life,” Schirmer says. “Every day, there was a new saint’s story.”

Giffey’s stories are reflected in his art as well. The walls are lined with life-sized icons of saints in a procession leading to the rotunda. Two small wings, or transepts, are dominated by paintings of St. George and St. Demetrius, leading to scenes from the New Testament. All of this draws the eye forward to the apse behind the altar, where a 10-foot-tall figure of the Virgin Mary is curved into the back wall; the child Jesus sits in her lap.

Her figure draws the eye up the curved walls to the four pendentives that support the dome. On these vaulted corners are the authors of the Gospels. The drum of the dome is ringed by 12 prophets, and upon its ceiling is the Christ. Giffey explains this last part is tradition: “The ceiling of the church represents Heaven, so a picture of Jesus is always painted there.”

All of these figures wear robes of vibrant yet earthy colors, and are splashed with gold leaf halos. The whole piece is unified by a background of a deep Magritte blue that washes over the entire church, making these saints, prophets and scribes born over a span of thousands of years feel as though they are of one world. The separate pieces are woven together with patterned bands and lines of scripture written in both English and Greek.

Giffey began painting Assumption in 1979 and continues to this day. He has painted nearly 100 figures. In September 2017, he added the first piece to a new lobby expansion. He estimates that he has put in 8,000 hours since first installing the Pantocrator piece, the Christ found in the dome. That adds up to four years total. As a frame of reference, this is the same amount of time that Michelangelo took to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

To paint icons is to be a storyteller in static imagery. The tales that Giffey lays out are not just a reflection of scripture; they portray the world that Giffey has known as an activist, a journalist, a soldier and a Christian. “It’s so easy to put the pictures up on the wall and pretend ‘Oh, what a wonderful world this is.’ It’s not,” says Giffey. “It’s a very imperfect world and I think we’re struggling with that really now in this era.” The weary-eyed saints that line the walls of the church are examples to follow in these times, says Giffey: “They themselves were imperfect and yet they had a certain courage and will to pursue what they believe.”

It was a long road that brought Giffey the short distance from his parents’ dairy farm near Ripon, Wisconsin, to this church in Madison. After a brief stint at Oshkosh State (now UW-Oshkosh), he dropped out to travel the country. In 1964, he was drafted into the Army and sent to Vietnam as a combat journalist. In 1966, he was discharged and found work as a reporter for the Appleton Post-Crescent.

Around this time, he befriended Jesus Salas, a local organizer for the migrant farmer labor unions. The two founded Voz Mexicana, a bilingual newspaper focusing on labor rights for migrant workers. They soon joined with the activist Cesar Chavez to organize grape boycott committees throughout Wisconsin to protest the unfair work practices of California grape growers. “We managed to reduce the amount of table grapes that were imported to Wisconsin by nearly 50 percent,” says Giffey. Later, he moved to the Rio Grande valley to recruit for Chavez’s United Farm Workers’ union in South Texas.

“I came from war to war, in a sense, a kind of human rights war,” says Giffey. “There’s a series of little towns along the river on the U.S. side of the border, and they were notoriously racist, anti-union and hostile to everything we represented.” He was hassled by customs officials whenever he crossed the border from Mexico and was jailed briefly for taking photos of a picket line.

He moved to Austin and began looking for ways to help process the harsh realities he had witnessed both in Vietnam and in the labor struggles in the Southwest. One way was through painting. He began selling art on the street, brightly colored, strange landscapes. “People called them primitive fantasies,” says Giffey, who did not study art in college.

Around this same time, his spiritual path led him to an Orthodox church. “I felt a need to go on a spiritual pilgrimage,” says Giffey. “Eastern Christianity answered my need for private meditation combined with mysticism, ritual, music, art and tradition.” He was captivated by the iconography. In 1974, he returned to his home state; his parents were aging, and he missed the Midwest. “When I came back to Wisconsin I exhausted the UW library because it had all these books of iconography,” says Giffey.

Iconography, in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, is a style of art that goes back to the late Roman Empire when Byzantium — modern-day Istanbul — became a cultural and religious center. Easily identifiable by the flat, perspective-free style, this is not a photo-realistic art. The heavy lines, unnatural shadows and stylized facial features are not meant to be taken as literal interpretations; they are representations of saints and prophets. What makes them particularly haunting are their eyes: They stare straight out at the observer. That’s no accident, says Giffey: “[Icons] look out at us because they are trying to communicate with us. They are very direct. They are not smiling. The hope is to represent spiritual properties like strength, sobriety, courage and forthrightness. That is why they are looking out.”

In 1977, Giffey traveled to Greece, India, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. “I had no idea that I would work for years making icons for Assumption when I first went to Greece,” says Giffey. But he kept going back, to learn the iconography and seek out mentors. “The Greek artists were very generous,” says Giffey. “I visited monasteries in Mount Athos where this tradition has been preserved for centuries. I watched and I helped and I climbed around on their scaffolds and I spent a lot of time observing the use of icons.” When he returned, he began envisioning his masterpiece.

Although he is working in an ancient style, following centuries-old rules, Giffey has been granted artistic license in his work at Assumption and found ways to reflect his commitment to social justice and pacifism. “The work is within a tradition, but it is creative,” says Giffey. “My wife Nancy compares it to music: If you gave a song by Mahler to 10 sopranos and told them to rehearse it and come back to perform it a month later, they would all use the same notations, but their interpretations would vary.” Giffey brings a Western influence into his work. There are traces of Cubism in the background images. The influence of Midwestern regionalist artists such as Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton can also be found in his paintings’ gracefully curving lines.

John Barker, retired UW-Madison professor of Byzantine history and member of Assumption’s congregation (and Isthmus classical music critic), observes that Giffey’s training in Greece honed his skills, but did not rigidly define it. “David studied that style and technique, but made it his own, not through imitation but by knowing assimilation. He brought his artistic sensibilities to his church connections.”

Giffey has also made a point of bringing gender equity to the walls of the church, distinguishing him from other iconographers. Pointing to the drum of the dome, he lists the figures he has painted: “Esther, Rebecca, Ruth… This is the only church I’ve been in where the figures are an approximately equal between the genders. The other churches I’ve been to have shown the prophets to be all men. [In Madison], half the people who come to church here are women or girls. Visual aids and role models are important to both genders.”

Schirmer, Giffey’s former Sunday school student, says Giffey led workshops on iconography for parish members “He would always encourage us to do icons of women saints, and that felt special,” says Schirmer, describing Giffey’s “de-sensationalized” take on Mary Magdalene. “She was a pretty cool, independent woman who got a bad rap from traditional interpretations of the Bible because of some supposed prostitution suspicion. That re-framing had an impact on me.”

Giffey’s pacifism is also represented in his artistic works. A longtime member of Veterans For Peace, he resists bringing images of gore into the church. He points out his painting of St. Demetrius, a Roman soldier punished by being forced into the gladiator’s pit for converting to Christianity. In the painting, Demetrius stands above his opponent, spear in hand, appearing to be poised to strike. This is, in fact, the moment when Demetrius stayed his hand, refusing to kill. On the opposite wall, St. George fights the dragon. “I tried to make the dragon as sympathetic as possible,” says Giffey.

This sensibility carries over to work he did at St. John the Evangelist Catholic Church in Spring Green, the only non-Orthodox church he has worked in. He was commissioned to paint the 14 Stations of the Cross, the story of Jesus’s procession from trial to death. The paintings themselves are simple and straightforward, except for one. The 11th Station shows the moment of Crucifixion, when the nails are being driven in. “That was one I spent special attention on. I struggle with certain traditional images, particularly in the Western churches [in which] Jesus looks so dead and tortured.”

Giffey’s 11th Station shows a centurion with hammer and nail ready, standing in the palm of a giant hand. This choice replaces the horror of the moment with the wonder of the miracle to come.

Giffey also departs from his Greek forbears by painting in acrylic on canvas, rather than directly onto plaster walls. Giffey paints the backgrounds directly on the wall, but then attaches icons over them, using plaster to cover the edges. He did not originate this technique, but he finds it ideal for the space he is working in. It avoids cluttering up the space with ladders and scaffolds for months on end, and there is an architectural reason as well. “Buildings in this hemisphere are built of sheet rock and two-by-fours. If I spent nine months painting the ceiling of the dome onto the plaster and the roof leaked it would destroy the painting,” says Giffey. “This way, if necessary, we could … chip the plaster back and peel the canvas off and it wouldn’t damage it.”

Destruction nearly came one night in 2001. A candle was accidentally left burning in the church’s narthex. It tipped over and caused a carpet fire that smoldered through the night. The church was spared the flame, but it suffered from the smoke. By the time the fire department arrived, the entire interior was, in Giffey’s words, “blackened.” For six months, services were held in the basement while Giffey and a crew of art conservators worked to bring the art back to life. “Inch by inch [we] cleaned every single icon.” Due to his technique and the paints used — water-based acrylics — he says, “I didn’t have to retouch a thing.”

“I really prefer painting to cleaning,” he adds.

Father Michael Vanderhoef has been here through it all. The priest at Assumption for 10 years, he has worshipped there since childhood. He calls Giffey “a family member.” Other churches, he says, “have someone else come in and do all the iconography and they’re gone. He didn’t just put up the icons and disappear.”

The church has changed over the years. “This is an incredibly diverse church,” says Giffey. “We have people who come from all over. North Africa, Syria, the Middle East, because for years this was the only Orthodox church in town.”

“I’ve seen it expand from just a little rectangular church to its building out and the dome being put up and David putting his icons up through the years,” adds Vanderhoef. For Midwestern Christians used to modest facilities, entering Assumption can be an eye-opening experience. “Some people come in and say ‘Oh my gosh.’ It’s sensory overload,” says Vanderhoef. “More are overwhelmed in a very positive way, but I have a very dear friend of mine who’s Lutheran who doesn’t come around much because he literally leaves with a headache. He says, ‘I’m a simple white wall, red carpet, wood pew person, and to come in here is, like, whoa!’ It is a different tradition.”

But Vanderhoef and the congregation appreciate the continuity that Giffey brings — and his stories. “This is a story not only of our holy traditions and our Bible, but our church. He continues to add to the story.”

Above the exit of the church, Giffey has painted four buildings; one is easily recognized as Assumption. The other three are plain Midwestern houses. As you step outside you see that the painted buildings are representations of the houses of 7th Street. This is Giffey’s playful way of showing that the church’s little corner of Madison is its own part of the larger story of the Greek Orthodox faith.

Likewise, the larger story of Giffey’s life can be seen in his paintings, both secular and religious. Long Shadow, his series based on his memories of Vietnam, was displayed in 2016 at Madison College, and then in Neillsville, Wisconsin. He created four murals for the Boys & Girls Club of Dane County, where he and his wife worked for years as teachers. These murals show a brief history of labor unions, the cause to which he devoted so much of his youth. His love for playing and watching basketball is represented in his quirkiest work, The Colleagues, 14 life-sized Byzantine-style portraits of the 1988 Milwaukee Bucks that get pulled out of storage for exhibition every few years.

A mural showing the history of Black Earth at the State Bank of Cross Plains at Black Earth is personal in its own way. It is the bank that loaned him and his wife Nancy money for a house. In the kitchen, 35 years after that loan went through, he still speaks in appreciation that they would do such a thing: “Artists are rewarded in many ways, but not financially.” He states this as a fact he is resolved to live with, not as a complaint. “I also am convinced that it’s necessary to choose a lifestyle that doesn’t require an overabundance of material things,” he adds.

Their house is a work of art in itself: A beautifully converted barn built into a hillside southwest of Arena. “Ninety percent of the house is recycled,” says Nancy, an artist and educator. “Everything but the plumbing and the electricity. Stuff people threw away, because we didn’t have the money for anything else.” David and Nancy each have a studio. David’s is a large space two stories high, right off the living room and kitchen. The wall where he pins up his canvases has become the kind of accidental abstract painting found in artists’ studios made up of traces of colors from projects he has done over the years. There are remnants of the art that came before in the vibrant blues, reds and yellows found throughout the church.

Assumption recently built a large exo-narthex, giving Giffey a beautiful new blank canvas to work with. The first piece he added in September depicts two angels holding up a large disc upon which sits the Virgin Mary, a smaller version of the image found in the church behind the altar. On her lap, the child Jesus holds a scroll showing that he is a teacher. Upon closer examination, it becomes clear that the angels are not holding up the virgin and child. It only looks that way because of the traditional flat perspective of iconography. The angels are, in fact, holding up a picture of Mary and Jesus. It is an icon holding an icon.

“People ask me how much more do you want to do?” says Giffey. “I have to decide that. I feel capable now, but who knows if I have two years, one year, 10 years, 20 years? I don’t know. I would love to do this whole area with scenes from the life of Mary.”

Giffey is wasting no time. At his home studio, he has begun putting together the pieces of a painting that will greet worshipers as they enter the building depicting Mary’s early childhood. Showing multiple points in time in one image, it is complex without being confusing, and from the early sketches it should be a stunning visual introduction to the other images in the church.

“There’s a need on my part to make the icons as beautiful as possible,” says Giffey. “As long as they tell the story they need to tell.”