And sometimes, for reasons redacted in the documents, the weapons simply miss. In April 2016 the military reported that it had killed a notorious Australian ISIS recruiter, Neil Prakash, in a strike on a house in East Mosul. Months later, very much alive, he was arrested crossing from Syria into Turkey. Four civilians died in the strike, according to the Pentagon.

Yet despite this unrelenting toll, the military’s system for examining civilian casualties rarely functions as a tool to teach or assess blame.

Not only do the records contain no findings of wrongdoing or disciplinary action, but in only one instance is there is a “possible violation” of the rules of engagement. That stemmed from a breach in the procedure for identifying a target. Full investigations were recommended in fewer than 12 percent of the credible cases.

In many cases, the command that approved a strike was responsible for examining it, too. And those examinations were often based on incorrect or incomplete evidence. Military officials interviewed survivors or witnesses in only two cases. Civilian-casualty reports were regularly dismissed because video showed no bodies in the rubble, yet the footage was often too brief to make a true determination.

In his response to The Times, Captain Urban said, “An honest mistake, on a strike taken with the best available information and in keeping with mission requirements that results in civilian casualties, is not, in and of itself, a cause for disciplinary actions as set forth in the law of armed conflict.”

American officials had an opportunity to mine the documents for root causes and patterns of error in 2018, when the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the National Defense University undertook a study of civilian deaths. But one of the researchers who sought to analyze the documents in aggregate told The Times that almost all of his findings had been cut from the report. Another high-level study of the air campaign has never been made public.

In the end, what emerges from the more than 5,400 pages of records is an institutional acceptance of an inevitable collateral toll. In the logic of the military, a strike, however deadly to civilians, is acceptable as long as it has been properly decided and approved — the proportionality of military gain to civilian danger weighed — in accordance with the chain of command.

Lawrence Lewis, the former Pentagon and State Department adviser whose analysis for the 2018 study was quashed, said in an interview that the military’s technological prowess, and the highly bureaucratized system for assessing how it is employed, may actually serve an unspoken purpose: to create greater legal and moral space for greater risk.

“Now we can take strikes in city streets, because we have Hellfire missiles, and we have fancy things with blades,” he said. “We develop all these capabilities, but we don’t use them to buy down risk for civilians. We just use them so we can make attacks that maybe we couldn’t do before.”

The Promise of Precision

The new way of war came to fruition in the wake of the 2009 surge of American troops into Afghanistan, which brought some stability but never turned the war around.

By the end of 2014, with NATO’s mission also ending, President Obama declared America’s ground war essentially done. Henceforth, the United States would primarily provide air support and advice for Afghan forces battling the Taliban.

At roughly the same time, as Islamic State fighters swept through Mosul and massacred thousands of Yazidi Kurds at Mount Sinjar, Mr. Obama authorized a campaign of airstrikes against ISIS targets and in support of allied forces in Iraq and Syria.

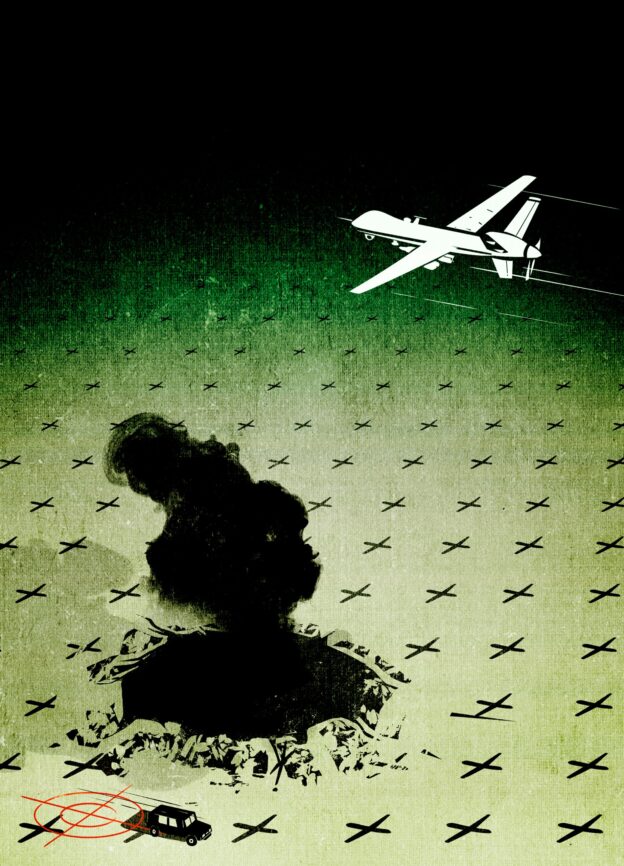

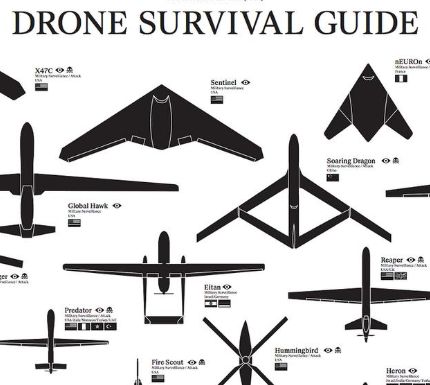

The weaponry was hardly untested. This high-tech arsenal, increasingly sophisticated, had been critical to success in the 1991 Persian Gulf war, in NATO’s 1999 campaign in the Balkans, and more recently in Yemen and Somalia. By the time of the wars in the Middle East, the MQ-9 Reaper drone, outfitted with laser-guided Hellfire missiles, had become the surveillance and attack vehicle of choice.

At an ever-quickening pace over the next five years, and as the administration of Mr. Obama gave way to that of Donald J. Trump, American forces would execute more than 50,000 airstrikes in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan, in accordance with a rigorous approval process that prized being “discriminate,” “proportional” and in compliance with the law of armed conflict. Not only would this be the most precise air campaign ever; it would be the most transparent.

The only official accounting of that promise is the hidden Pentagon documents.

They were obtained through Freedom of Information requests beginning in March 2017 and lawsuits filed against the Defense Department and U.S. Central Command. To date, The Times has received 1,311 out of at least 2,866 reports — known as credibility assessments — examining airstrikes in Iraq and Syria between September 2014 and January 2018. Requests for records from Afghanistan are the subject of a new lawsuit.

Each report is the fruit of a review process that begins when a potential civilian-casualty incident is identified by the military or, more frequently, alleged by an outside source — a nongovernmental organization, a news outlet or social media.

Assessment experts classify allegations into two categories. A case is “credible” if it is deemed “more likely than not” that the airstrike caused civilian casualties. In the reports examined by The Times, 216 cases were deemed credible. “Noncredible” cases fail to meet that standard — often because there is no record of a strike at the place and time in question, or because the available evidence is considered insufficiently specific or simply weak.

Until now, fewer than 20 of these assessments dating to late 2014 have been made public.

To assess the military’s assessments, between late 2016 and this past June, The Times visited the sites of 60 incidents deemed credible in Iraq and Syria, as well as three dozen others deemed noncredible or not yet assessed. (It also visited dozens of strike sites in Afghanistan.) In 35 credible cases, it was possible to locate the precise impact area and find survivors and witnesses on the ground. Then the reporting included touring wreckage; collecting photo and video evidence; and verifying casualties through death certificates, government IDs and hospital records.

Frequently the reporting closely matched basic information from the documents. But the detailed accounts that ultimately emerged from the rubbled ground were often in stark contrast to what had been assessed from the air.

… more …

The war against ISIS heralded the dawn of “strike cells” — remote operations centers from which most airstrikes were directed and controlled. These war rooms synergized the myriad players — pilots, sensor operators, intelligence experts, ground forces, weaponeering specialists, civilian-casualty-mitigation analysts, lawyers, even weather officers. Strike cells boasted at times that, with their video feeds and surveillance aircraft, they could understand what was happening on the battlefield as well as if they were there themselves.

As the war intensified and ground commanders won greater authority to call in strikes, the cells expanded, with a small number of Americans embedded with allies on the battlefield. The cells were seen as so successful that they made their way to Afghanistan, too. And as the Trump administration sought to pressure the Taliban into a deal, decision-making authority for airstrikes was often pushed further down the chain of command.

The cells conducted “dynamic strikes” — identified and executed within minutes or hours in the flow of war, accounting for an overwhelming majority of the air campaign. “Deliberate” strikes, which were preplanned — extensively vetted, often filmed over weeks or months and analyzed by several working groups — decreased over time.

In both scenarios, the targeting process essentially boiled down to two questions: Could the presumed enemy target be positively identified? And would any harm to civilians be proportional, in line with the law of armed conflict — or would it exceed the “expected military advantage gained”?

For positive identification, the officer designated with strike approval needed “reasonable certainty” that the target performed a function for the adversary. That could be relatively straightforward, as when the target was a fighter firing directly on friendly forces. But a more ambiguous target, like a suspected ISIS headquarters, might require further surveillance.

To determine proportionality, analysts evaluated whether the target was used exclusively by the enemy or might also be used by civilians, then assessed civilians’ “pattern of life.” Ultimately, they would calculate how many civilians were likely to be killed or wounded.

For deliberate strikes, this generally entailed an exhaustive “collateral damage estimate,” a computer calculation of the expected civilian casualty count, based on a mix of factors: the pattern of life, the population density, the specific weapon being used, the kind of structure being targeted — a concrete building, an aluminum shed, a mud hut. The officer approving the strike would weigh that estimate with other factors, such as the potential for secondary blasts from explosive materials nearby.

For dynamic strikes, the process could be vastly compressed. Especially if there was a threat to friendly forces or some other urgency, strike cells were more likely to rely on an impromptu assessment of a video feed.

Either way, based on that calculation, the military was required to take “feasible precautions” to mitigate civilian harm. The greater the likelihood of someone being in the wrong place at the wrong time, the more precautions taken — say, by deploying more-precise weaponry to limit the blast radius or by attacking when the fewest civilians were predicted to be present.

The military does not provide a precise definition of what is proportional. Essentially, the expected civilian toll was proportional if the officer making that determination reasonably believed it to be so, and if it did not exceed a “noncombatant cutoff value.” Otherwise, officials say, the target would be discarded.

The final official step was a legal review. But efforts to protect civilians could continue until moments before a weapon was fired. From the cockpit, pilots could select how a weapon detonated — upon impact or with a delayed fuse. Or they could call an “abort,” if, for example, a civilian was spotted walking into the target area.

Under the right circumstances, this process could result in a strike so precise that it would destroy the section of a house filled with enemy fighters and leave the rest of the building intact.

As Iraqi forces approached Qusay Saad’s home in East Mosul on Jan. 12, 2017, ISIS forced his family to move to an area still under its control. They found refuge in his brother’s abandoned house in al-Faisaliya.

Through a night of gunfire and explosions, Mr. Saad and his wife, Zuhour, comforted their three children and prayed that Iraqi forces would reach them. Then ISIS ordered them to move again, into an abandoned school next door with two other families. That was the building observed in the chat on Jan. 13, 2017.

The first airstrike hit as the Saad family sat down to breakfast. Mr. Saad recalls concrete blocks pressing down on his head, and his wife screaming. A man from one of the other families lifted away the blocks, and he quickly wrested his 14-month-old daughter, Aisha, from the rubble and handed her to his wife.

The second strike came just as he turned to free his 7-year-old son, Muhammad.

“The strike was unbelievable,” he said. “An entire three-story house was just crushed.”

Three members of another family escaped. Mr. Saad could not find his wife, their 4-year-old son, Abdulrahman, or Aisha. But Muhammad was alive, his thigh split open. Bleeding from the head, Mr. Saad picked up the boy and fled.

It would be two months before he could recover the bodies. The Iraqi government offered no help. So the family paid to excavate the site. Mr. Saad watched as his wife and two youngest children were lifted out. Aisha’s head was missing, but her little body was in her mother’s arms.

They were buried not far from their home, which Mr. Saad has kept as it was when they all lived there. Sometimes, his brother said, he spends whole nights at the graveyard.

Last month, The Times told him of the findings of the military’s assessment. It offers this account:

The target was a building assessed as harboring four ISIS fighters. A review of the imagery revealed that after the first strike, which because of a “weapon malfunction” only partly collapsed the building, four adults and four children could be seen moving in its center. The building was hit again and fully collapsed. Later, three people emerged. The strike team did not report any civilians in the vicinity, and because of the drone’s angle, a view of the eight people in the building after the first strike “was obscured.”

The allegation was deemed credible, with eight civilians killed, but no further investigation was ordered. Eight “enemies” were also killed, the document said.

When told of the Army’s findings, Mr. Saad could not understand how a military with such a wealth of information could have failed to see them — or how the pursuit of fighters he never saw could justify leveling a building full of families. If the Americans would show him the video, he said, he would show them Mosul.

“They have to come here and see with their own eyes,” he said, adding, “What happened wasn’t liberation. It was the destruction of humanity.”

How Deadly Failures Happen

Last May, the Pentagon’s inspector general completed a classified report evaluating the policies for ensuring that “only valid military targets are struck,” and that “damage to property and loss of civilian life is mitigated to the maximum extent possible.”

A redacted version, echoing similar studies by other agencies in recent years, declares the targeting process to be sound.

The Pentagon’s own assessments tell a far richer story.

The documents often do not articulate precise causes, and in many cases, several factors coalesced into a deadly failure. But The Times’s analysis of the 216 cases deemed credible, together with its reporting on the ground, reveals several distinct patterns of failure.

Positive identification of the enemy is one of the pillars of the targeting process, yet ordinary citizens were routinely mistaken for combatants.

In a dissenting footnote to the 2018 Joint Chiefs’ study, Mr. Lewis and a colleague cited research showing that misidentification was one of the two leading causes of civilian casualties in American military operations. With few troops on the ground, they wrote, “it is reasonable to expect a systematic undercounting of misidentifications in U.S. military reports.”

Indeed, according to the Pentagon records, misidentification was involved in only 4 percent of cases. At the casualty sites visited by The Times, misidentification was a major factor in 17 percent of incidents, but accounted for nearly a third of civilian deaths and injuries.

At times, the error involved quicksilver intelligence of an imminent threat. In The Times’s ground sample, though, misidentification occurred just as frequently in strikes planned far in advance — as in a January 2017 strike on an ISIS “foreign fighter headquarters” in East Mosul that killed 16 people in what turned out to be three civilian homes. Three ISIS buildings down the street were untouched.

Yet in case after case, the misidentification appears to be less a matter of confusion than of confirmation bias.

That was what happened on Nov. 20, 2016, after a Special Operations task force received a report of an ISIS explosives factory in a Syrian village north of Raqqa. In a walled compound, operators spotted “white bags,” assessed to be ammonium nitrate. Two trucks with a dozen men departed, stopped at various ISIS checkpoints, drove to a building “associated with previous ISIS activity,” then returned to the compound. The first strike targeted one truck, which caused “secondary explosions.” On the evidence of those blasts and the “white bags,” operators received approval to strike three buildings. After impact, two “squirters” fled the westernmost building. That building and another were struck again.

The findings of the military’s review, begun after online reports that a strike in the same area had killed nine civilians and injured more than a dozen, contradicted nearly all of the original intelligence.

Examining scans of the compound, analysts detected no ammonium nitrate. The presumed secondary explosions were actually reflections from a nearby building, and one of the “squirters” was a child. Finally, a six-month time lapse of imagery showed that the compound was “more likely a cotton gin than a factory” for explosives. Two civilians were killed, the report said. (The task force continued to call the gin a legitimate target, citing a news report that ISIS controlled three-quarters of Syria’s cotton production.)

Several months later, in Iraq, American forces received intelligence about a suspected car bomb — a dark-colored, heavily armored vehicle moving through the Wadi Hajar neighborhood of West Mosul.

Scanning a surveillance feed, an air-support coordinator quickly homed in on a possible match: a green vehicle whose windows appeared to be covered over. He did not see any signs of reinforced armor, but positively identified both the green car and a closely trailing white vehicle as car bombs.

Both vehicles traveled away from the front line and stopped at an intersection where several people were gathered on a covered section of sidewalk. The driver of the first car got out and joined the group. The target authority approved the strike.

The targeted vehicle “sustained a direct hit,” according to the military assessment. The group on the sidewalk “sustained weapons effects.”

But the review of the footage found no evidence that the vehicle was a car bomb. There was no telltale secondary explosion. Nor was the car heavily armored. And though the people on the sidewalk were visible in the footage, they were never mentioned in the pre-strike chat.

The full picture, which the targeting team involved in the strike failed to see, emerged when The Times visited Wadi Hajar earlier this year.

Ordered by ISIS to leave the neighborhood, Majid Mahmoud Ahmed, his wife and two children had piled into their blue — not green — Opel Astra station wagon. Following close behind in a white car were his brother, Firas, and his family. At an intersection where other fleeing residents had gathered, Mr. Ahmed spotted his friend Muhammad Jamaal Muhammad waving and got out to say hello. As another neighbor approached, the airstrike hit.

“I remember there was a big explosion, and I fainted,” recalled Abdul Hakeem Abdullah Hamash Al Aqidi, an elderly man who had been standing by his door at the intersection. He lost an eye and had to have a plate implanted in his injured left leg. His son’s left leg had to be amputated.

In all, seven local people — including the four members of the Ahmed family — were killed. Mr. Mohamed, who had waved to Mr. Ahmed, cannot banish from his mind the image of his friend’s wife, Hiba Bashir, burned into the seat, still holding her infant son in her lap.

The military spokesman, Captain Urban, acknowledged that “confirmation bias is a real concern,” citing the Kabul airstrike in August that killed the 10 members of a family. “There is more work to do on this,” he said.

Failing to Detect Civilians

If the military often mistook civilians for enemy fighters, frequently it simply failed to see or understand that they were there. That was a factor in a fifth of the cases in the Pentagon documents, and a slightly smaller fraction of the casualties. However, it accounted for 37 percent of credible cases, and nearly three-fourths of the total civilian deaths and injuries at the sites visited by The Times.

Captain Urban said the targeting process had been vastly complicated by enemies who “plan, resource and base themselves in and among local populace.”

“They do not present themselves in large formations,” he added, “do not fight coalition forces with conventional tactics, and use geography and terrain in ways not conducive in every way to easy targeting solutions. Moreover, they often and deliberately use civilians as human shields, and they do not subscribe to anything remotely like the law of armed conflict to which we subscribe.”

Even so, the documents show that frequently, instead of extended surveillance, analysts relied on brief “collateral scans” — as little as 11 seconds long — in determining that civilians were not in the area. The footage was often limited by shortages of surveillance drones, particularly during the battles to retake Mosul and Raqqa.

In a number of cases, targets that had been placed on “no-strike lists” because attacking them would violate laws of war — a school, a bakery, a civilian hospital — were removed after the military mistakenly judged that they were now used exclusively by the enemy.

In Mosul in February 2017, a hospital was taken off the list after the military concluded that civilians had left the area, and that the building was being used only as an ISIS headquarters and propaganda center. The week before the strike, according to the report, analysts had examined still images of children “interacting” with the hospital but had determined that striking at night would “alleviate collateral concerns.” Four civilians were killed and six injured.

For the military’s analysts, studying the “pattern of life” is a crucial step in predicting collateral damage. But to examine the documents and interview local people is to understand how often unseen civilians might have been seen, or their presence at least suspected, had the military had a more intimate knowledge of the war-torn fabric of everyday life.

In some documents, as evidence of no civilian presence, military officials state that people would leave their homes at the sound of approaching aircraft. The reality is starkly different: Neighbors would huddle together, seeking communal sanctuary in a house or group of houses, invisible to surveillance drones.

Many of the deadliest airstrikes happened this way. Among them was the strike at the Syrian hamlet of Tokhar.

In July 2016, a Special Operations task force identified a large group of ISIS fighters two kilometers from where U.S.-backed forces were fighting ISIS. They observed the fighters traveling in pickups known as “bongo trucks” to three “staging areas” where no civilians were present. The fighters, they concluded, were assembling for a counterattack. Shortly before 3 a.m., they bombed the three staging sites and five vehicles, confident of killing 85 ISIS fighters.

Almost immediately, reports of a vast civilian death toll surfaced online. The task force conducted a full investigation and determined that between seven and 24 civilians “intermixed with the fighters” might have been killed.

The Times visited Tokhar in December 2018. Surviving villagers gave this account:

That night, as they had every night for a month, some 200 villagers had trekked to the outer edge of the hamlet and taken shelter in four homes at the farthest remove from the quickening battle.

There was no evidence, they said, that ISIS had been near any of the four houses. In fact, residents said drones had been flying overhead for weeks, giving them solace that coalition forces knew they were there.

The Times documented the names of civilians killed in each of the four houses, corroborating details with open-source information, local journalists and others on the ground, and determined that more than 120 people died. There were few young men left to pull bodies from the rubble. It took nearly two weeks, and still some were never found. If the full death toll were acknowledged, Tokhar would be the largest civilian casualty incident the United States has admitted to in the air war against ISIS.

Saif Saleh, 8 years old at the time, awoke that early morning to the collapsing walls, his arm trapped under debris. His parents used up every favor to collect $6,000 for surgery to graft skin from his leg.

Asked what he would like to tell the American military, Saif’s father said, “We want to say that you should be sure the area is empty or that there are no civilians before you bomb.”

The military investigation found that there was no evidence of negligence or wrongdoing; that the “policies, procedures and practices” were “sufficient for continued operations”; and that “no further action” was necessary. No condolence payments were authorized.

Overlooking Flawed Intelligence

Often, civilians were killed in strikes executed in the face of incomplete, outdated or ambiguous intelligence. Several such factors came together in a strike that killed at least 10 civilians in Tabqa, Syria, in March 2017.

As American-backed forces prepared to recapture the city, west of Raqqa, military officials approved strikes on a group of ISIS targets: two headquarters, a police station and a weapons factory. Each strike went as planned, according to initial assessments. Then came reports of civilian casualties.

The military review found that the intelligence for both headquarters was based on single reports from months before. (The targets had been identified earlier, but for strategic advantage, commanders had decided to wait until Syrian Democratic Forces were pushing into Tabqa.) The intelligence package on the first building warned that there was “insufficient” evidence to corroborate the judgment, relied on to remove the building from a restricted-targeting list, that it was used solely by ISIS; the report said simply that an ISIS emir had frequented the site.

Similarly, the review found that the intelligence did not support the view that the second headquarters was used exclusively by ISIS. What’s more, even though both headquarters were in densely populated areas with residential structures nearby, there was insufficient footage to assess the presence of civilians — one minute of video of the first target and less than two of the second.

The review also raised serious questions about the quality of intelligence for the two other targets.

Sometimes, the problem was less the quantity of video than the quality

Analysts at the military’s Combined Air Operations Center in Qatar saw this clearly when they reviewed 17 minutes of grainy footage that preceded a Nov. 13, 2015, strike on an ISIS “defensive fighting position” in Ramadi. Using the center’s 62-inch high-definition TV, they concluded that what had been identified as an “unknown heavy object” being dragged into a building was actually “a person of small stature,” “consistent with how a child would appear standing next to an adult.”

Often the overhead surveillance camera missed people simply sitting or standing under something, doing the most quotidian things.

June 15, 2016: An ISIS fighter on a motorcycle turned onto a secondary road near Mosul University. It was Ramadan; the shops and stalls were teeming with people. Among the five civilians also killed and four wounded in the strike:

Abdul Wahab Adnan Qassim, killed by shrapnel, had been standing in the tree-filled courtyard of his house.

A father and daughter, killed by glass and shrapnel, had been sitting in a car nearby.

Nashwan Abdul Majeed Abdul Hakeem Al Radwani, killed by shrapnel, had been standing under the awning of the popular Hammurabi Ice Cream Shop.

More than half of the cases the military deemed credible involved someone entering the target frame in the moments between a weapon’s firing and impact, as in a March 2017 strike in Mosul when shrapnel killed a man pushing a cart down a road near an ISIS mortar tube.

These deaths, which account for 10 percent of acknowledged civilian casualties, are often framed as unavoidable accidents. In the Mosul strike that killed the man with the cart, operators had already twice aborted weapons releases because civilians had entered the frame — demonstrating concerted efforts to avert danger. Yet the systematic nature of the problem suggests the military could be doing more.

Indeed, the review of a February 2017 strike on a “high value individual” at a funeral in Mosul that injured two civilians includes some recommendations. While noting that the civilians’ presence “could not be predicted to reasonable certainty,” it adds that an additional surveillance aircraft could have provided a more encompassing view. (Because of the target’s importance, two aircraft were used to zoom in, rather than out, on the wider scene.) Yet again surveillance drones were in short supply.

In the late spring of 2015, as ISIS continued to prove resilient in carrying out attacks and retaining territory, American targeteers and weapons specialists prepared a nighttime airstrike on a car-bomb factory in the industrial district of Hawija, north of Baghdad. Occupied apartment houses ringed the area. But the nearest “collateral concern” was assessed to be a “shed.”

Not long before, dozens of displaced families, unable to afford rent, had also begun squatting in the abandoned houses scattered through the industrial zone. Among them were Khadijah Yaseen and her family, who had fled the fighting in their hometown, Yathrib.

The night of June 2 was particularly hot, so the family slept outside. They woke to screaming and the sound of the jets.

“There was fire everywhere,” Ms. Yaseen recalled when The Times met her at a displaced persons camp in October 2016. Most of those killed were from squatter families like hers. “You couldn’t count them. There were so many people that died.”

As many as 70, a military investigation found. Ms. Yaseen lost three grandchildren: 13-year-old Muhammad, 12-year-old Ahmed and a 3-year-old girl, Zahra.

Hawija is among the deadliest examples of the failure to predict the collateral consequences of striking weapons caches or other targets with the potential for secondary explosions. Such explosions often reached far beyond the expected blast radius; they accounted for nearly a third of all civilian casualties acknowledged by the military and half of all civilian deaths and injuries at the sites visited by The Times.

Although the American military planned the Hawija strike, the bombs were dropped by the air force of the Netherlands. There, the case became a cause célèbre after it emerged that the defense minister had worked to suppress the findings of the military investigation.

In the report of the investigation, targeteers and weapons experts describe the ultimately disastrous calculations taken to win approval for the strike. They worked and reworked the target, carefully calculating what kinds of munitions to use until their model concluded — despite the fact that they would be striking a car-bomb factory with apartment buildings nearby — that there would be no civilian deaths. (The Dutch military would only carry out strikes with an expected civilian-casualty rate of zero.)

The document describes a secondary explosion that produced a “visible shock wave” extending more than 750 feet from the target.

“That is massive, to be able to see a shock wave like that on a video,” said a former high-level official involved in the air campaign against ISIS, speaking on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. The only comparable explosion he’d seen, he said, was the 2020 blast that devastated the port of Beirut.

Among the sites visited by The Times, at least half of the strikes with secondary explosions involved targets — like a power station or a factory for improvised explosive devices — that the military could have predicted would produce such blasts.

However, at other times it was unaware of both a weapons cache and a civilian presence. That was the case in the largest civilian casualty incident the military has admitted in the war, the March 17, 2017, airstrike on two ISIS snipers in the Mosul al-Jadida neighborhood that killed at least 103 civilians.

Failures of Accountability

On Jan. 6, 2017, Rafi Al Iraqi woke to the sound of a bomb close by. Another hit next door. Moments later, his own house was struck. He could hear his oldest son, Hamoody, screaming in the wreckage. “I just gave him to some people to take him to the hospital,” Mr. Al Iraqi recalled. “Then I went back in to find my other children.”

What happened next was captured on video taken by ISIS’ media agency, which often visited blast sites for propaganda.

Rescuers emerged holding limp bodies. Mr. Al Iraqi’s daughter, Nour, was alive. “I took her with my own hands to the hospital,” he recalled this past June, in his most recent interview with The Times. “But by then, she had died.” A nearby house for ISIS fighters was untouched.

Soon, via the ISIS video and news reports, word spread online that three families had been targeted in the Zerai neighborhood near Mosul’s Grand Mosque. In all, 16 civilians were killed, including three of Mr. Al Iraqi’s children and his mother-in-law. Hamoody’s leg was lacerated.

The military began a civilian-casualty assessment, which found that there had been a single strike in Zerai that day — on a house assessed to be used exclusively as an ISIS “foreign fighter headquarters” and “artillery staging location.” The strike had been preplanned, with no expected civilian casualties.

The post-strike footage showed no civilians killed or injured. The post-strike chat did not indicate the presence of civilians, though it did mention a wounded man — judged to be an ISIS fighter — being helped from the ruins.

The footage was 1 minute and 22 seconds long. The allegation was deemed noncredible. Officially, 16 people had not died that day in Zerai. (The Pentagon finally acknowledged the casualties in September 2020, after years of follow-up by The Times.)

Except for the rare instances of revelation and subsequent outcry, the Pentagon’s brief published reports on the minority of cases it finds credible are the only public acknowledgment of the air war’s civilian toll.

The Times’s reporting in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan points to the broader truth.

In addition to the finding that many allegations of civilian casualties were erroneously dismissed, The Times discovered that even when civilian deaths were acknowledged, they were often significantly undercounted.

Roughly 37 percent of the allegations deemed credible stemmed from prior ground investigations by journalists or nongovernmental organizations; in those cases, the acknowledged death tolls roughly tracked outside reporting. But in the other cases, The Times’s own reporting found that the civilian toll was nearly double that acknowledged by the military. (That did not include ISIS fighters’ wives and children, whose information was difficult to verify.)

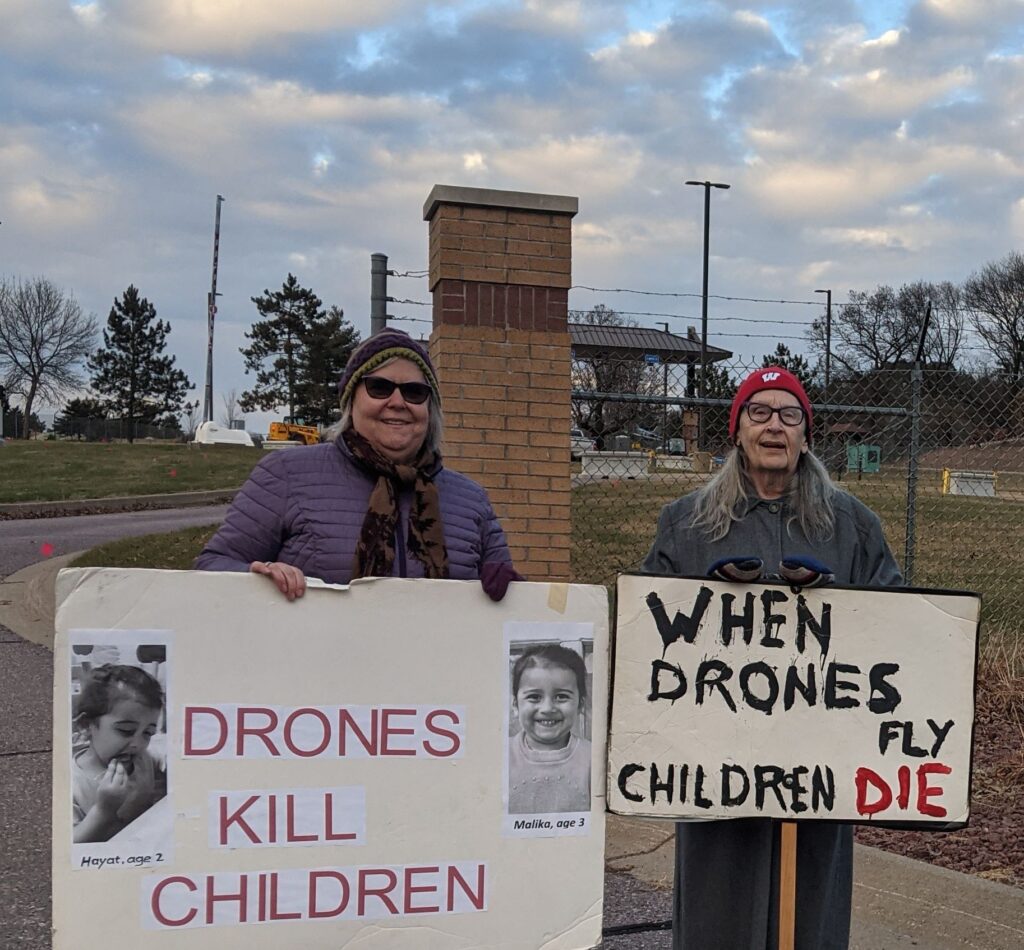

The documents identify children killed or injured in 27 percent of cases; in The Times’s ground reporting it was 62 percent. In 40 percent of the sites visited, survivors had been left with significant disabilities, which were not tracked by the military.

Beyond the casualty count, the structure and execution of the assessments do not encourage the regular examination of immediate lessons or deeper trends.

The records obtained by The Times, some significantly redacted, range from short first-impression reports to more formal credibility assessments. The reports generally contain a narrative drawn from the strike’s “target package” — including intelligence about the target, the civilian-casualty estimate, actions to mitigate civilian harm, video footage and chat logs tracking each step of the process.

Not only was there no record of disciplinary action, or full investigations in roughly 9 of every 10 cases, but only a quarter included any further review, recommendations or lessons learned. Even the architecture of the forms makes it difficult to analyze causes in aggregate; they do not have specific boxes for specific factors involved in a fatal error. There are a few places to record proximate causes or lessons learned, but those fields are mostly empty or redacted. Records are often incomplete, missing attachments or were only partially entered into shared databases.

In many cases, the unit that executed a strike also ended up investigating it; their assessments often included minimal information. For example, a Special Operations unit’s rationale for rejecting allegations that a December 2016 airstrike near Raqqa had killed as many as nine civilians consisted of a single paragraph stating that it had reviewed its strikes in the area and found “no evidence of possible civilian casualties.” There was no further information or detail from the footage.

The Times found that such omissions, as well as redactions and missing documents, were often associated with Talon Anvil, the Special Operations unit that carried out the recently revealed airstrike that killed dozens of civilians in Syria in 2019.

Of the 1,311 assessments from the Pentagon, in only one did investigators visit the site of a strike. In only two did they interview witnesses or survivors.

Captain Urban, the military spokesman, said that in hostile territory, investigators might be unable to visit a blast site and interview “personnel on the ground.”

Instead, often the resounding piece of evidence studied was video recorded in the wake of a strike. Yet just as poor or insufficient footage frequently contributed to deadly targeting failures, so did it hamstring efforts to examine them.

Often, the footage was only seconds or minutes long, in many cases too brief to see rescuers carrying survivors from a collapsed building. (Frequently, rescuers would wait before approaching a bombed area, for fear of being misidentified and provoking a second strike, known in the military as a “double tap.”) Often, images were obscured by the smoke of the blast.

In an interview — speaking anonymously because of a nondisclosure agreement — an analyst who captures strike imagery said superior officers would often “tell the cameras to look somewhere else” because “they knew if they’d just hit a bad target.”

And at times, there was simply no footage for review, which became the basis for rejecting the allegation. That was often because of “equipment error,” because no aircraft had “observed or recorded the strike,” or because the unit could not or would not find the footage or had not preserved it as required.

In a number of cases, compelling allegations were dismissed because the claim’s details did not precisely match the imagery.

For example, when Airwars — the leading source of civilian casualty allegations referred to the military — reported that a strike in East Mosul in April 2015 had killed dozens of civilian rescuers, the allegation was rejected because of “discrepancies in eyewitness accounts.” Despite accurately testifying that three bombs had struck an electric substation, a witness said the third had come a quarter-hour after the second and had not exploded; the document described that as “inconsistent” with the military’s imagery and strike report. (The allegation was later deemed credible after The Times visited the site and told the military that at least 18 civilians had been killed and more than a dozen wounded.)

Even when allegations were deemed credible, the military often undercounted the toll because victims, unseen by the overhead camera before the strike, remained invisible in the aftermath. Case in point: the 2016 Ramadan bombing near Mosul University that killed five civilians and wounded four. The military reported injuries to two civilians who had been in the pre-strike footage.

When the military receives an allegation of civilian casualties, it runs through a checklist to determine whether the case merits further inquiry. Most never reach the point of video review. About a quarter of the noncredible cases were summarily closed because they lacked sufficient information or detail, such as a specific location or 48-hour time frame. But more than half were rejected, in some cases erroneously, because the military could find no record of corroborating strikes in the geographic area identified in the allegation — or because there were too many potential matches, and too little detailed information.

That information would be found in official logs maintained by different strike authorities. But The Times found numerous instances in which the logs were incomplete or inaccurate: Often, records show, the coalition knew its logs were flawed.

Frequently, cases were closed because the military said it lacked the information to pinpoint the neighborhood in question. Sometimes that conclusion was rooted in misunderstandings of local custom and culture.

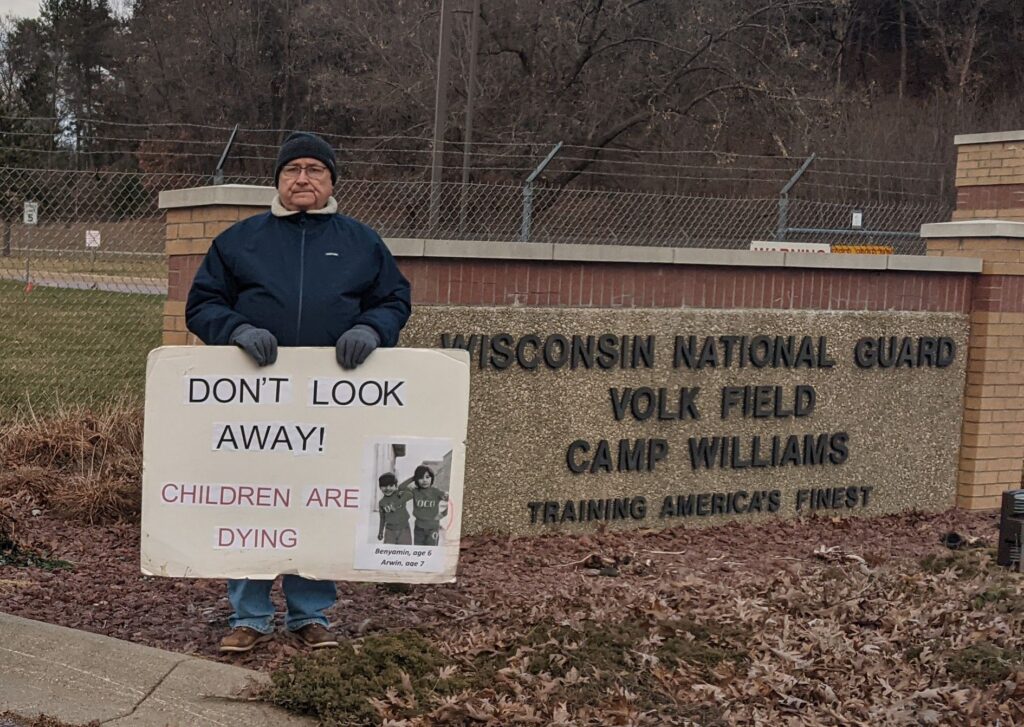

Caskets for the dead are carried toward a gravesite as relatives and friends attend a mass funeral for members of a family that is said to have been killed in a U.S. drone airstrike, in Kabul, Afghanistan, on Aug. 30, 2021. (MARCUS YAM/LOS ANGELES TIMES/TNS)

In January 2017, citing insufficient information, an officer quickly closed a case based on social media reports that civilians had been killed in a strike on a funeral in the al Shifaa neighborhood of West Mosul. Fruitlessly, the officer had searched logs for potentially corroborating strikes in the cemetery closest to that neighborhood.

However, as reflected in a graphic video accompanying the initial reports, the strike had not taken place at a cemetery: A thumbnail depicted the entrance to a house. In fact, Muslim funerals are rarely held at cemeteries. What’s more, Muslims bury the dead quickly, and it had been four days since this man, Col. Aziz Ahmed Aziz Sanjari, had died.

The colonel’s death had brought many members of the Sanjari family’s tribe to their home to mourn. It was a sunny afternoon, so more than a dozen people sat outside. They could hear a drone humming above, but were unworried. It was a common occurrence. A few minutes later, the bomb hit. Eleven people were killed, The Times found.

‘Sometimes Bad Things Happen’

Captain Urban acknowledged that, “In some cases our assessment of the numbers of civilian casualties does not always match that of outside groups, and we acknowledge that those numbers may change over time as well.

“We do the best we can, given the circumstances, to understand fully the effects of our operations and the harm done to innocent life. That we sometimes do not always arrive at the same conclusion of outside groups does not diminish the sincerity with which we strive to get it right.”

Several Pentagon studies, rendered in military bureaucratese, have observed some of the failures of accountability. The April 2018 Joint Chiefs of Staff examination of civilian deaths from airstrikes in the Middle East and Africa found that “feedback to subordinate commands on the cause and/or lessons learned from a civilian casualty incident is inconsistent.” The recent Pentagon Inspector General report spoke of “omissions.”

Yet for the most part, these reports do not speak to questions of how airstrikes repeatedly go wrong.

Mr. Lewis, the co-author whose efforts to analyze the assessments in aggregate were excised from the Joint Chiefs’ study, said the report instead relied primarily on interviews with assessment officers. They were able to detect certain patterns — especially casualties from secondary explosions and from people entering the target frame after a weapon’s firing — but few of the systematic reasons behind the bulk of civilian deaths.

The Times asked him why the military would develop such intricate procedures to prevent civilian casualties, and then assess them, but not prioritize documenting or studying causes and lessons learned. Not only does the system provide legitimacy for the military’s actions, he said; it also allows the United States to boast of a process that is a global model of accountability.

The former high-level American official in the campaign against ISIS said the procedures served an additional purpose — to provide a “psychological veneer” for the people involved: “We did the process. We did what we needed to do. Sometimes bad things happen.”

He said that after returning from his post, anguished by what he had seen, he had started therapy. He pointed to Raqqa, rendered a necropolis by American-led airstrikes, and compared it to the ruins of Aleppo, which was bombed by the Russians without the American military’s sophisticated considerations of proportionality — the collateral damage estimates, no-strike lists or rules of engagement.

“Eventually I stopped saying that this was the most precise bombing campaign in the history of warfare,” he said. “So what? It doesn’t matter that this was the most precise bombing campaign and the city looks like this.”

In Afghanistan

All the boys and men of Band-e-Timor knew that when the Toyota Hiluxes came, you should run for your life.

People called them wegos. At the wheel were Afghan paramilitary forces who usually set out on full-moon nights at the fork in the road before Lashkar Gah, charging through the village of Barang straddling the Kandahar-Helmand border and into other parts of Band-e-Timor, “capturing everyone: old men, young men, everyone,” said a resident named Matiullah.

It did not matter if you were not Taliban, people said. If you were male, the Afghan forces would arrest you, simply to collect a bounty for your release. If you were old or feeble, the price was just over $500; a man in his prime would fetch twice that. “You would have to sell your cow or your land to get your relatives released,” said Rahmatullah, a village resident. Often, it was the poorest who would run.

On the night of Jan. 31, 2018, the moon was especially bright. The wegos, as usual, came accompanied by what villagers said were American aircraft. Hidayatullah, a driver by profession, three days from marrying, knew he could not afford the bounty and the wedding, so he drove out into the desert. Then an airstrike found him, said Matiullah, who is his cousin. Dozens of other civilians, mistaken for Taliban as they fled on foot and motorbike across Band-e-Timor, died in the raid as well.

The August drone strike in Kabul that killed an Afghan aid worker and nine of his relatives grabbed the world’s attention. But most American airstrikes in Afghanistan took place far from the cities, in remote areas where cameras were not filming, mobile lines were often cut and the internet was nonexistent.

America’s longest war was, in many ways, its least transparent. For years, these rural battlefields were largely off-limits to American reporters. But after the Taliban returned to power in August, Afghanistan’s hinterlands opened up.

The Times arrived in Barang a little over a month later, visiting 15 households in this hamlet of mud homes and farmland, and also interviewing tribal elders and others across Band-e-Timor. Most said they had never spoken to a journalist before. The accounts they gave — consistently and reliably, in hourslong interviews — help explain how America lost the country, how its war of airstrikes and support of corrupt security forces paved the way for the Taliban’s return.

On average, each household lost five civilian family members. An overwhelming majority of these deaths were caused by airstrikes, most during wego raids. Many people admitted they had relatives who were Taliban fighters, but civilians accounted for most of those lost:

A father killed in an airstrike while running for the forest. A nephew killed as he slept with his flock of sheep. An uncle shot by American soldiers as he went to the bazaar to buy okra for dinner.

At the sound of helicopters, Hajji Muhammad Ismail Agha’s sons had bounded for the desert. The “foreign helicopters” fired on them. One son, Nour Muhammad, was killed; the other, Hajji Muhammad, survived. “How could the planes tell the difference between a civilian and a Taliban?” the father asked. “He was killed just a little far from here. I watched it happen.”

None of these incidents were mentioned in Pentagon press releases. Few were tallied in United Nations counts. So isolated from the Afghan government were residents that when asked for their loved ones’ death certificates, they asked where they might obtain them. Instead, to verify deaths, The Times visited tombstones, in graveyards littered across the desert.”