REDWOOD VALLEY, Calif. — “After hiding all night in the mountains, Air Force Capt. Kevin Larson crouched behind a boulder and watched the forest through his breath, waiting for the police he knew would come. It was Jan. 19, 2020. He was clinging to an assault rifle with 30 rounds and a conviction that, after all he had been through, there was no way he was going to prison.

Captain Larson was a drone pilot — one of the best. He flew the heavily armed MQ-9 Reaper, and in 650 combat missions between 2013 and 2018, he had launched at least 188 airstrikes, earned 20 medals for achievement and killed a top man on the United States’ most-wanted-terrorist list.

The 32-year-old pilot kept a handwritten thank-you note on his refrigerator from the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. He was proud of it but would not say what for, because like nearly everything he did in the drone program, it was a secret. He had to keep the details locked behind the high-security doors at Creech Air Force Base in Indian Springs, Nev.

There were also things he was not proud of locked behind those doors — things his family believes eventually left him cornered in the mountains, gripping a rifle.

In the Air Force, drone pilots did not pick the targets. That was the job of someone pilots called “the customer.” The customer might be a conventional ground force commander, the C.I.A. or a classified Special Operations strike cell. It did not matter. The customer got what the customer wanted.

And sometimes what the customer wanted did not seem right. There were missile strikes so hasty that they hit women and children, attacks built on such flimsy intelligence that they made targets of ordinary villagers, and classified rules of engagement that allowed the customer to knowingly kill up to 20 civilians when taking out an enemy. Crews had to watch it all in color and high definition.

Captain Larson tried to bury his doubts. At home in Las Vegas, he exuded a carefree confidence. He loved to go out dancing and was so strikingly handsome that he did side work as a model. He drove an electric-blue Corvette convertible and a tricked-out blue Jeep and had a beautiful new wife.

But tendrils of distress would occasionally poke up, in a comment before bed or a grim joke at the bar. Once, in 2017, his father pressed him about his work, and Captain Larson described a mission in which the customer told him to track and kill a suspected Al Qaeda member. Then, he said, the customer told him to use the Reaper’s high-definition camera to follow the man’s body to the cemetery and kill everyone who attended the funeral.

“He never really talked about what he did — he couldn’t,” said his father, Darold Larson. “But he would say things like that, and it made you know it was bothering him. He said he was being forced to do things that went against his moral compass.”

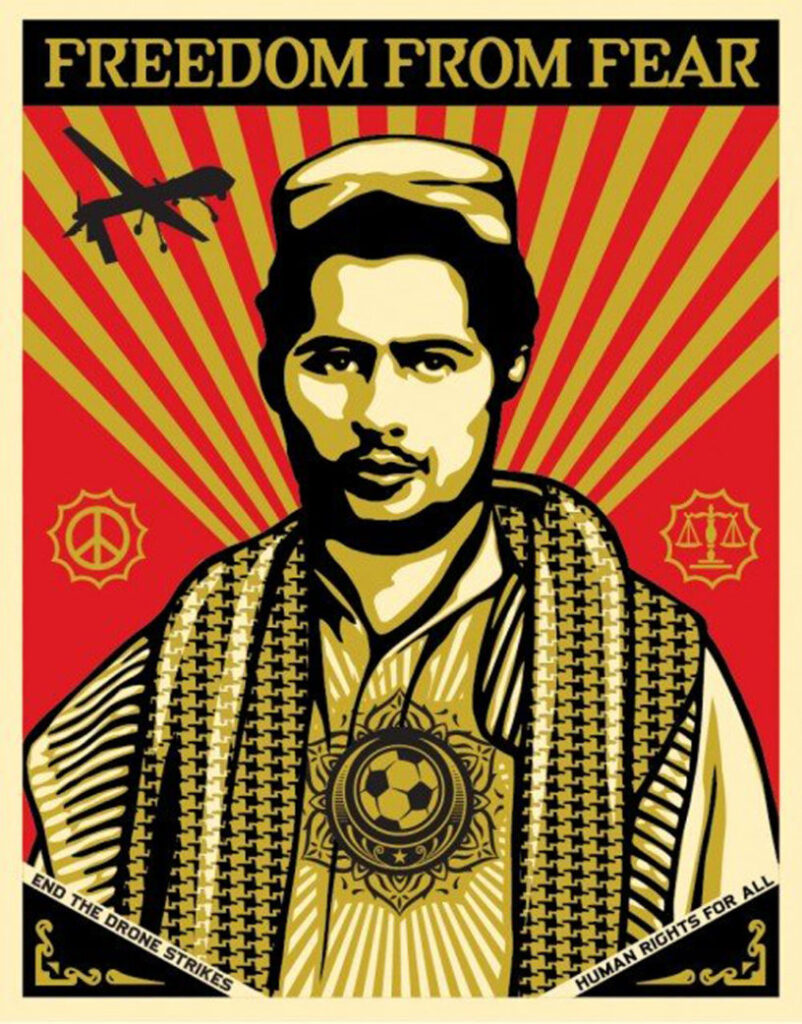

Drones were billed as a better way to wage war — a tool that could kill with precision from thousands of miles away, keep American service members safe and often get them home in time for dinner. The drone program started in 2001 as a small, tightly controlled operation hunting high-level terrorist targets. But during the past decade, as the battle against the Islamic State intensified and the Afghanistan war dragged on, the fleet grew larger, the targets more numerous and more commonplace. Over time, the rules meant to protect civilians broke down, recent investigations by The New York Times have shown, and the number of innocent people killed in America’s air wars grew to be far larger than the Pentagon would publicly admit.

Captain Larson’s story, woven together with those of other drone crew members, reveals an unseen toll on the other end of those remote-controlled strikes.

Drone crews have launched more missiles and killed more people than nearly anyone else in the military in the past decade, but the military did not count them as combat troops. Because they were not deployed, they seldom got the same recovery periods or mental-health screenings as other fighters. Instead they were treated as office workers, expected to show up for endless shifts in a forever war.

Under unrelenting stress, several former crew members said, people broke down. Drinking and divorce became common. Some left the operations floor in tears. Others attempted suicide. And the military failed to recognize the full impact. Despite hundreds of missions, Captain Larson’s personnel file, under the heading “COMBAT SERVICE,” offers only a single word: “none.”

Drone crew members said in interviews that, while killing remotely is different from killing on the ground, it still carves deep scars.

“In many ways it’s more intense,” said Neal Scheuneman, a drone sensor operator who retired as a master sergeant from the Air Force in 2019. “A fighter jet might see a target for 20 minutes. We had to watch a target for days, weeks and even months. We saw him play with his kids. We saw him interact with his family. We watched his whole life unfold. You are remote but also very much connected. Then one day, when all parameters are met, you kill him. Then you watch the death. You see the remorse and the burial. People often think that this job is going to be like a video game, and I have to warn them, there is no reset button.”

In the wake of The Times’s investigations, the Pentagon has vowed to strengthen controls on airstrikes and improve how it investigates claims of civilian deaths. The Air Force is also providing more mental-health services for drone crews to address the lapses of the past, said the commander of the 432nd Wing at Creech, Col. Eric Schmidt.

“We are not physically in harm’s way, and yet at the same time we are observing a battlefield, and we are seeing some scenes or being part of them. We have seen the effects that can have on people,” Colonel Schmidt said. In the past, he said, remote warfare was not seen as real combat, and there was a stigma against seeking help. “I’m proud to say, we have come a long way,” he added. “It’s sad that we had to.”

Captain Larson tried to cope with the trauma by using psychedelic drugs. That became another secret he had to keep. Eventually the Air Force found out. He was charged with using and distributing illegal drugs and stripped of his flight status. His marriage fell apart, and he was put on trial, facing a possible prison term of more than 20 years.

Understand Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

The invasive symptoms of PTSD can affect combat veterans and civilians alike. Early intervention is critical for managing the condition.

- Removing the Stigma: Misconceptions about how PTSD develops and its symptoms, can prevent people from seeking treatment.

- Psychedelic Drugs: As studies explore the therapeutic value of substances like MDMA, veterans are becoming unlikely advocates for their decriminalization.

- Virtual Reality: A treatment using new technology to immerse patients in a simulation of a memory could help them overcome trauma.

- Pandemic Trauma: Covid-19 has exacerbated mental health issues among medical workers, putting them at great risk of developing PTSD.

Because he was not a conventional combat veteran, there was no required psychological evaluation to see what influence his war-fighting experience might have had on his misconduct. At his trial, no one mentioned the 188 classified missile strikes or the funeral he had targeted. In January 2020, he was quickly convicted.

Desperate to avoid prison, reeling from what he saw as a betrayal by the military he had dedicated his life to, Captain Larson ran.

A Vexing Moral Landscape

Captain Larson grew up in Yakima, Wash., the son of police officers. He was a straight-and-narrow Eagle Scout who went to church nearly every Sunday and once admonished a longtime friend to stay away from marijuana. At the University of Washington, where he was an honors student, he joined R.O.T.C. and the Civil Air Patrol, set on becoming a fighter pilot.

The Air Force had other plans. By the time he was commissioned in 2012, the Pentagon had a developed seemingly insatiable appetite for drones, and the Air Force was struggling to keep up. That year it turned out more drone pilots than traditional fighter pilots and still could not meet the demand.

“He was sobbing when he got the news. So disappointed. He wanted to fly,” his mother, Laura Larson, said in an interview. “But once he started, he enjoyed it. He really felt like he was doing something important.”

Captain Larson was assigned to the 867th Attack Squadron at Creech — a unit that pilots say worked largely with the C.I.A. and Joint Special Operations Command. The drone crews operated out of a cluster of shipping containers in a remote patch of desert. Each crew had three members: a sensor operator to guide the surveillance camera and targeting laser, an intelligence analyst to interpret and document the video feeds, and a pilot to fly the Reaper and push the red button that launched its Hellfire missiles.

The specifics of Captain Larson’s missions are largely a mystery. He kept the classified details hidden from his parents and former wife. His closest friends in the attack squadron and dozens of other current and former crew members did not respond to requests for interviews; secrecy laws and nondisclosure agreements make it a crime to discuss classified details.

But several pilots, sensor operators and intelligence analysts who did the same type of work in other squadrons spoke with The Times about unclassified details and described their struggles with the same punishing workload and vexing moral landscape.

More than 2,300 service members are currently assigned to drone crews. Early in the program, they said, missions seemed well run. Officials carefully chose their targets and took steps to minimize civilian deaths.

“We would watch a high-value target for months, gathering intelligence and waiting for the exact right time to strike,” said James Klein, a former Air Force captain who flew Reapers at Creech from 2014 to 2018. “It was the right way to use the weapon.”

But in December 2016, the Obama administration loosened the rules amid the escalating fight against the Islamic State, pushing the authority to approve airstrikes deep down into the ranks. The next year, the Trump administration secretly loosened them further. Decisions on high-value targets that once had been reserved for generals or even the president were effectively handed off to enlisted Special Operations soldiers. The customer increasingly turned drones on low-level combatants. Strikes once carried out only after rigorous intelligence-gathering and approval processes were often ordered up on the fly, hitting schools, markets and large groups of women and children.

Before the rules changed, Mr. Klein said, his squadron launched about 16 airstrikes in two years. Afterward, it conducted them almost daily.

Once, Mr. Klein said, the customer pressed him to fire on two men walking by a river in Syria, saying they were carrying weapons over their shoulders. The weapons turned out to be fishing poles, Mr. Klein said, and though the customer argued that the men could still be a threat, he persuaded the customer not to strike.

In another instance, he said, a fellow pilot was ordered to attack a suspected Islamic State fighter who was pushing another man in a wheelchair on a busy city street. The strike killed one of the men; it also killed three passers-by.

“There was no reason to take that shot,” Mr. Klein said. “I talked to the pilot after, and she was in tears. She didn’t fly again for a long time and ended up leaving for good.”

Squadrons did little to address bad strikes if there was no pilot error. It was seen as the customer’s problem. Crews filed civilian casualty reports, but the investigative process was so faulty that they rarely saw any impact; often they would not even get a response.

Over time, Mr. Klein grew angry and depressed. His marriage began to crumble.

“I started to dread going in to work,” he said. “Everyone kind of expects you to do that stuff and just be fine, but it ate away at us.”

Eventually, he refused to fire any more missiles. The Air Force moved him to a noncombat role, and a few years later, in 2020, he retired, one of many disillusioned drone operators who quietly dropped out, he said.

“We were so isolated, that I’m not sure anyone saw it,’ he said. “The biggest tell is that very few people stayed in the field. They just couldn’t take it.”

‘Soul Fatigue’

In her job as a police officer, Captain Larson’s mother conducted stress debriefings after traumatic events. When officers in her department shot someone, they were required to take time off and meet with a psychologist. As part of the healing process, everyone present at the scene was required to sit down and talk through what had happened. She was not aware of any of that happening with her son.

“At one point I pulled him aside and told him, ‘If things start bothering you, you and your friends need to talk about it,’” Ms. Larson said. “He just smiled and said he was fine. But I think he was struggling more than he ever let on.”

The Air Force has no requirement to give drone crews the mental health evaluations mandated for deployed troops, but it has surveyed the drone force for more than a decade and consistently found high levels of stress, cynicism and emotional exhaustion. In one study, 20 percent of crew members reported clinical levels of emotional distress — twice the rate among noncombat Air Force personnel. The proportion of crew members reporting post-traumatic stress disorder and thoughts of suicide was higher than in traditional aircrews.

Several factors contribute — workload, constantly changing shifts, leadership issues and combat exposure. But the most damaging, according to Wayne Chappelle, the Air Force psychologist leading the studies, is civilian deaths.

Seeing just one strike that causes unexpected civilian deaths can increase the risk of PTSD six to eight times, he said. A survey published in 2020, several years after the strike rules changed, found that 40 percent of drone crew members reported witnessing between one and five civilian killings. Seven percent had witnessed six or more.

“After something like that, people can have unresolved, disruptive emotional reactions,” Dr. Chappelle said. “We would assume that’s unhealthy — having intrusive thoughts, intrusive memories. I call that healthy and normal. What do you call someone who is OK with it?”

Having time off to process the trauma is vital, he said. But during the years when America was simultaneously fighting the Taliban, the Islamic State and Al Qaeda, that was nearly impossible.

Starting in 2015, the Air Force began embedding what it called human performance teams in some squadrons, staffed with chaplains, psychologists and operational physiologists offering a sympathetic ear, coping strategies and healthy practices to optimize performance.

“It’s a holistic team approach: mind, body and spirit,” said Capt. James Taylor, a chaplain at Creech. “I try to address the soul fatigue, the existential questions many people have to wrestle with in this work.”

But crews said the teams were only modestly effective. The stigma of seeking help keeps many crew members away, and there is a perception that the teams are too focused on keeping crews flying to address the root causes of trauma. Indeed, a 2018 survey found that only 8 percent of drone operators used the teams, and two-thirds of those experiencing emotional distress did not.

Instead, crew members said, they tend to work quietly, hoping to avoid a breakdown.

Bennett Miller was an intelligence analyst, trained to study the Reaper’s video feed. Working Special Operations missions in Syria and Afghanistan in 2019 and 2020 from Shaw Air Force Base in South Carolina, the former technical sergeant saw civilian casualties “almost monthly.”

“At first it didn’t bother me that much,” he said. “I thought it was part of going after the bad guys.”

Then, in late 2019, he said, his team tracked a man in Afghanistan who the customer said was a high-level Taliban financier. For a week, the crew watched the man feed his animals, eat with family in his courtyard and walk to a nearby village. Then the customer ordered the crew to kill him, and the pilot fired a missile as the man walked down the path from his house. Watching the video feed afterward, Mr. Miller saw the family gather the pieces of the man and bury them.

A week later, the Taliban financier’s name appeared again on the target list.

“We got the wrong guy. I had just killed someone’s dad,” Mr. Miller said. “I had watched his kids pick up the body parts. Then I had gone home and hugged my own kids.”

The same pattern occurred twice more, he said, yet the squadron leadership did nothing to address what was seen as the customer’s mistakes. Two years later, Mr. Miller was near tears when he described the strikes in an interview at his home. “What we had done was murder, and no one seemed to notice,” he said. “We just were told to move on.”

Mr. Miller grew sleepless and angry. “I couldn’t deal with the guilt or the anxiety of knowing that it was going to probably happen again,” he said. “I was caught in this trap where if I care about what is happening, it’s devastating. And if I don’t care, I lose who I am as a person.”

At Shaw, he said, his squadron did not have a human performance team. “We just had a squadron bar.”

In February 2020, he got home from a 15-hour night shift, locked himself in his bedroom, put a cocked revolver to his head and through the door told his wife that he could not take it anymore. He was hospitalized, diagnosed with PTSD and medically retired.

Beyond their modest standard pensions, veterans with combat-related injuries, even injuries suffered in training, get special compensation worth about $1,000 per month. Mr. Miller does not qualify, because the Department of Veterans Affairs does not consider drone missions combat.

“It’s like they are saying all the people we killed somehow don’t really count,” he said. “And neither do we.”

A Question of Forgiveness

In February 2018, Captain Larson and his wife, Bree Larson, got into an argument. She was angry at him for staying out all night and smashed his phone, she recalled in an interview. He dragged her out of the house and locked her out, barely clothed. The Las Vegas police came, and when they asked if there were any drugs or weapons in the house, Ms. Larson told them about the bag of psilocybin mushrooms her husband kept in the garage.

When she and Captain Larson had met in 2016, she said, he was already taking mushrooms once every few months, often with other pilots. He also took MDMA — known as ecstasy or molly — a few times a year. The drugs might have been illegal, but, he told her, they offered relief.

“He would just say he had a very stressful job and he needed it,” Ms. Larson said. “And you could tell. For weeks after, he was more relaxed, more focused, more loving. It seemed therapeutic.”

A growing number of combat veterans use the psychedelic drugs illicitly, amid mounting evidence that they are potent treatments for the psychological wounds of war. Both MDMA and psilocybin are expected to soon be approved for limited medical use by the Food and Drug Administration.

“It gave me a clarity and an honesty that allowed me to rewrite the narrative of my life,” according to a former Air Force officer who said he suffered from depression and moral injury after hundreds of Reaper missions; he asked not to be named in order to discuss the use of illegal drugs. “It led to some self-forgiveness. That was a huge first step.”

In Las Vegas, the civilian authorities were willing to forgive Captain Larson, but the Air Force charged him with a litany of crimes — drug possession and distribution, making false statements to Air Force investigators and a charge unique to the armed forces: conduct unbecoming of an officer. His squadron grounded him, forbade him to wear a flight suit and told him not to talk to fellow pilots. No one screened him for PTSD or other psychological injuries from his service, Ms. Larson said, adding, “I don’t think anyone realized it might be connected.”

As the prosecution plodded forward over two years, Captain Larson worked at the base gym and organized volunteer groups to do community service. He and his wife divorced. Struggling with his mental health, seeking productive ways to cope with the trauma, he read book after book on positive thinking and set up a special meditation room in his house, according to his girlfriend at the time, Becca Triano.

“I don’t know what he saw, what he dealt with,” she said. “What I did see toward the end was him really working hard to try to stay sane.”

The trial finally came in January, 2020. His former wife and a pilot friend testified about his drug use. The police produced the evidence. That was all.

After deliberating for a few hours on the morning of Jan. 17, the jury returned with guilty verdicts on nearly every count.

On the Run

The pilot would be sentenced after a break for lunch. His lawyer told him to be back in an hour. Instead he took off.

He loaded his Jeep with food and clothes and sped away, convinced that he was facing a long prison sentence, Ms. Triano said. Within hours, the Air Force had a warrant out for his arrest.

Captain Larson headed southwest to Los Angeles and stayed the night with a friend, then started heading north. By the afternoon of Saturday, Jan. 18, he was driving by vineyards and redwood groves on U.S. Route 101 in Mendocino County, north of San Francisco, when the California Highway Patrol spotted his Jeep and pulled him over.

Captain Larson stopped and waited calmly for the officer to walk up to his window. Then he gunned it — down the highway and onto a narrow dirt logging road that snaked up into the mountains. After several miles, he pulled off into the trees and hid. The police could not find him, but they knew something he did not: All the roads in the canyon were dead ends, and officers were blocking the only way out.

Night fell. Nothing to do but wait.

In the morning, during a briefing at the bottom of the canyon, records show, Air Force agents explained to the Mendocino County sheriff’s deputies that the wanted man was a deserter who had fled a drug conviction, was probably armed and possibly suicidal.

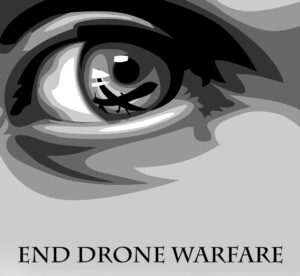

The officers drove up the canyon and spotted tire tracks on a narrow turnoff. Agents crept up on foot until they spotted the blue Jeep in the trees, but did not risk going farther. The deputies had a better option, something that could get a view of the Jeep without any danger. A small drone soon launched into the sky.

Captain Larson was hiding behind a mossy boulder. There was no phone service deep in the canyon, no way to call for whatever hope or solace he might have conjured. He could only record a video message for his family members. One by one, he told them that he loved them. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I won’t go to prison, so I’m going to end this. This was always the plan.”

There was a lot he did not explain — things that have kept his family and friends wondering in the years since. He did not talk about the hundreds of secret missions or their impact. He did not say what it had felt like to have his commanders stand by quietly as civilian deaths became routine, then stay just as quiet when a decorated pilot was prosecuted for drug possession. He did not talk about the other pilots who had done the same drugs and then avoided him like a virus after he got caught.

Perhaps he was planning to say more, but as he spoke into the phone camera, he was interrupted by an angry buzzing, like a swarm of bees.

“I can hear the drones,” he said. “They’re looking for me.”

Had they found him alive, his pursuers would have been able to tell him this: In the end, the Air Force had decided not to sentence him to prison, only to dismissal.

But now, just as Captain Larson had done countless times, the officers could only study the drone footage and parse the evidence — slumped behind the boulder, shot with his own assault rifle — of another unintended death.

originally New York Times

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK). You can find a list of additional resources at SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources.